Not long after spending 24 hours with artist William Kentridge I bought a butter dish. The purchase was prompted by a frivolous lunchtime conversation. It helps to know that Kentridge, South Africa’s best-known artist globally, whose 40-year career as draughtsman, printmaker, sculptor, filmmaker and theatre director is currently being surveyed by major museums in London, Los Angeles and Milwaukee, likes to eat lunch with his studio staff. The menu tends towards a miscellany of salads, cheeses, breads and – yes – hotdogs.

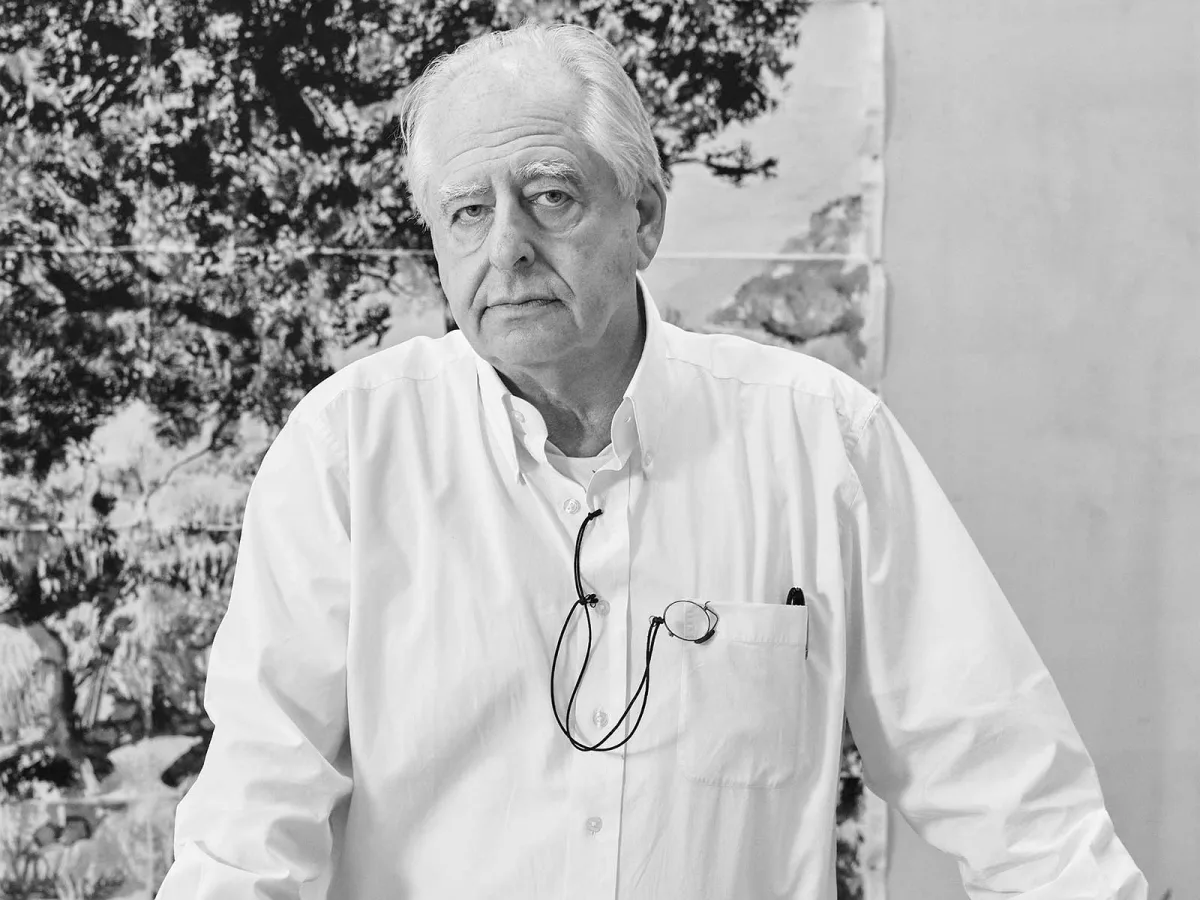

In summer, the fare is laid out in front of a Simon Stone mural on the north-facing patio of the Houghton home Kentridge grew up in as a child and returned to with his family in the late 1990s. But it is winter when I visit Kentridge to spend time and chat about his large-scale exhibition at London’s storied Royal Academy (RA). The artist, who wears a white button shirt and sober slacks no matter what, is seated indoors with more than a dozen staff. Their duties are diverse. Three are video editors working on a film created to accompany a live recital of Russian composer Dimitri Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony.

While Kentridge butters his bread I mention my dislike of people hacking wedges out of butter blocks. The grey-haired artist with aquiline nose and blue eyes thinks about my statement for a moment. He doesn’t mind that so much, he responds, but storing butter in its trade wrapper, now that’s in poor taste. Oops, I gulp, and swiftly move the conversation along. But let’s pause for a moment on Kentridge in the kitchen. One can learn a great deal seated at a dining table with Kentridge. For starters, he is a decent cook. For dinner he prepares a dish of boiled ox tongue served with an orange-infused mustard sauce and carrots.

I share the dinner with the artist and his Australian-born wife, Anne Stanwix, a physician specialising in rheumatology. Sweethearts since high school, the couple performed together in a leftist theatre troupe at university in the 1970s. Stanwix flits in and out of view in Kentridge’s artistic output. There she is, the naked muse in the artist’s magical 2003 film installation 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès. This appearance is not anomalous: there is strong biographical tide flowing through Kentridge’s work.

Professionally, Kentridge is known to be a connoisseur of African history, European opera, revolutionary Russian art, the poetry of Rilke, paintings of Édouard Manet and much besides. At home, these worldly interests dovetail with his instinctive pleasure in food and family. Family is important. After our meaty dinner, the artist takes a call from one of his two daughters. He shortly slips into the role of waving granddad on Facetime. Kentridge remains a dutiful son, too – the artist’s 99-year-old father, famed anti-apartheid lawyer Sir Sydney Kentridge, was chaperoned through a private preview of his son’s RA exhibition in September.

Kentridge’s family history can fill an entire book. I’ll be concise. The artist is the scion of driven and educated Lithuanian Jewish settlers who prospered in South Africa. They include the artist’s great-grandfather, Woolf Kantrovich, rabbi of the Vryheid, who anglicised the family surname to Kentridge in 1912. Irene Geffen, his maternal great-grandmother, was South Africa’s first female advocate. But I want to pause on his parliamentarian grandfather, lawyer Morris Kentridge, whose 1959 political memoir, I Recall, has a cover illustration depicting a portly Jewish man stuffed into a suit. He closely resembles the artist’s much-discussed fictional character of the Jewish robber baron, Soho Eckstein.

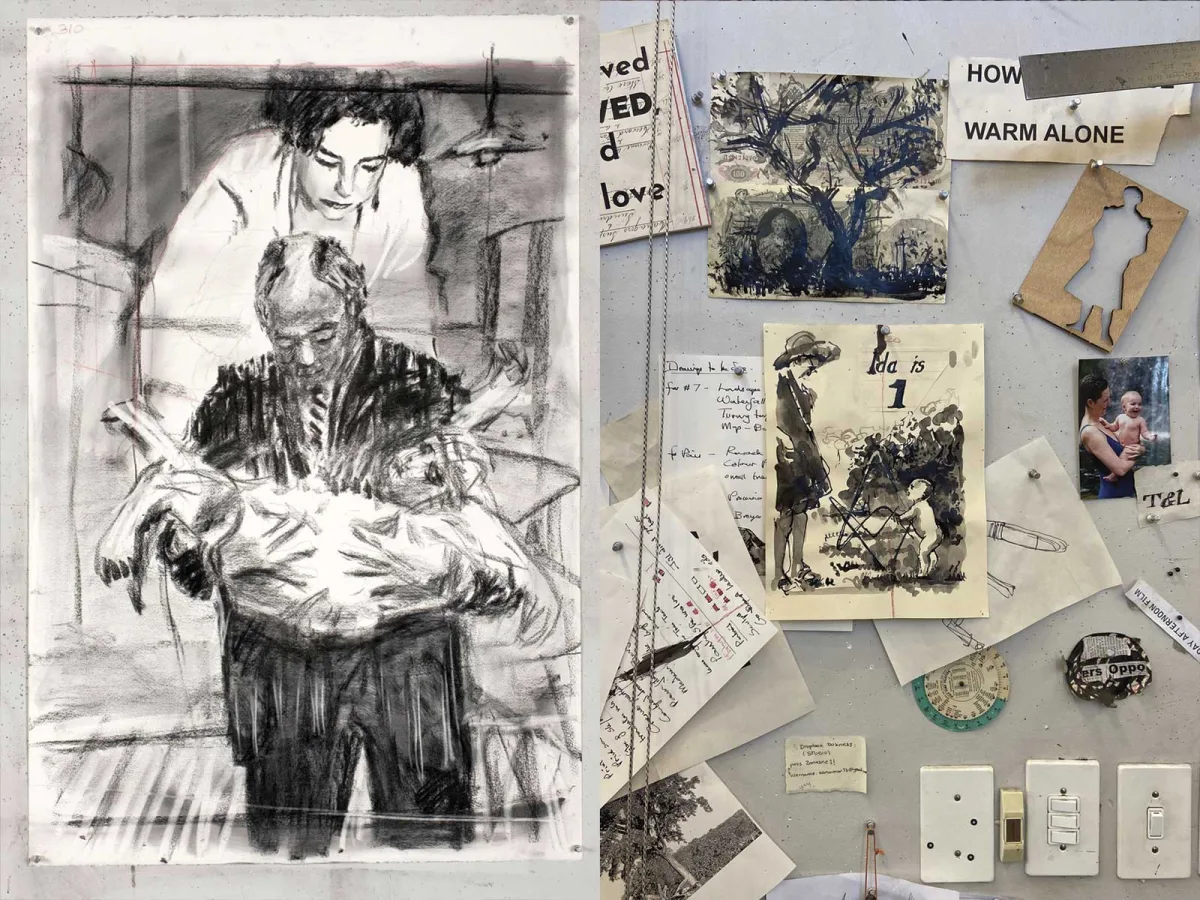

Kentridge’s Royal Academy show includes an entire room of Soho drawings and another devoted to the films in which Soho is the central protagonist. Soho’s provenance is complex. He was gestated in drawings Kentridge made in the 1970s and 80s for theatre and trade union posters. Soho came into sharper focus in the print suite Industry & Idleness (1986), which referenced English satirist William Hogarth and quoted scenes from Kentridge’s early adult years living in Bertrams.

“Soho was absolutely the industrialist taking over Johannesburg,” says Kentridge of the glutinous man in a pinstripe suited depicted in Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris (1989), the first of his celebrated stop-animation films from his on-going Drawings for Projection series. The artist is seated on a chaise lounge in his studio when he tells me this. Supper is done. Houghton twinkles in the night. Johannesburg is hushed. “When I had my first big exhibition in London at the Serpentine Galleries, in 1999, there was a whole complaint about anti-Semitism.”

The complaint was led by a prominent art critic but was secretly stoked by a South African émigré of Jewish parentage. The denouement to this painful episode in Kentridge’s career played itself out at a party in Plettenburg Bay many years later. Kentridge approached the aggrieved businessman and asked which had brought more dishonour to South Africa’s Jewry: his renderings of Soho or the émigré’s much-publicised banishment from the London Stock Exchange for shady dealings. “He stormed out of the party.”

While it is true that Soho was a cartoonish figure in Kentridge’s earliest films, over time he has emerged as a durable vehicle to explore the real-life burdens and existential responsibilities of living in contemporary South Africa. This transformation owes largely to Kentridge’s realisation that Soho was an alter ego. And so Soho’s portrayal has softened. He now also increasingly resembles the artist, especially in two recent films included in the RA show. Both are set in a transforming Johannesburg. City Deep (2020) juxtaposes scenes of culture and leisure with the illicit scavenger mining in the city’s many shuttered gold mines. Other Faces (2011) details the recycling of a mine dump and car accident involving Soho. The film is notable for its tender portrayals of the artist’s mother, lawyer Felicia Kentridge, who was rendered paralysed in later life by a degenerative disease. One moving drawing depicts Soho holding vigil over a bedridden woman.

Our conversation pivots from Soho to Russia. Kentridge’s new film, Oh to Believe in Another World, features dancers in elaborate costumes performing in grand neo-classical edifices made from painted cardboard and filmed in the artist’s studio. The film, which premièred in Switzerland and Italy over the European summer, explores Shostakovich’s complicated relationship with Russia under Stalin. Kentridge’s fascination with Russia is longstanding.

“I always had an interest since university days,” he says. “Is the liberal solution the only solution? What are other kinds of ways of thinking about it? The calamitous failures of the big ideas of socialism are questions that still seem so present. That is the reason for my interest in the new film with the Shostakovich music.”

Kentridge first visited Russia more than a decade ago.

“It was such a pleasure to see Moscow’s beautiful metro stations, which gave you sense of the dream of a people’s art. Moscow particularly is such a masculine society. The men drank vodka together, with women far at the edges. Here, the art world has always been quite feminine. Irma Stern is our superstar. When I started off, the heroes were largely women. Jo Smail was the flavour of the day, also Aileen Lipkin. Russia was a shock.”

I end my time with Kentridge by visiting the Centre for the Less Good Idea in Johannesburg’s Maboneng Precinct. Established by the artist in 2016 and named after a Tswana proverb (“If the good doctor can’t cure you, find the less good doctor”), the centre promotes collective thinking and collaborative artistic practices. The centre has hosted about 600 artists and presented nine seasons of productions to the public. In November, Houseboy, a two-hour performance with nine players workshopped at the centre and based on a 1956 novel by Cameroonian diplomat Ferdinand Oyono, will premiere in Los Angeles.

“It is an affirmation for collaboration,” Kentridge proudly tells, adding that the success of his large-scale theatrical productions The Head and the Load (2018) and Waiting for the Sibyl (2019) are directly attributable to the centre. “It has been very important in terms of my own work, meeting new people and collaborators. But it is a long-term test whether this kind of collaboration or improvisation is a legitimate, functional and productive way of arriving at something.”

Kentridge enters a rehearsal room. A small team of actors and stagehands are tinkering with a play featured in the seventh season. Kentridge, who in two days time will be in New York to receive an honorary doctorate from Columbia University, along with Hilary Clinton and Patti Smith, tells the team he can give them an hour. It is a productive hour. Ideas are traded. Sets refined. At one point Kentridge walks into the spotlight and begins an impromptu mime routine. He gesticulates. “Easy kind of farce like that,” he says. “Am I here? Or, you take out your wallet.” He replaces his wallet in his pocket, only to show amazement at its sudden disappearance. His private audience laughs. Kentridge is gloriously holding court, again.

William Kentridge at the Royal Academy, London, runs until 11 December 2022; William Kentridge: See for Yourself, The Warehouse, Milwaukee, runs until 16 December 2022; and William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows, The Broad, Los Angeles, runs until 9 April 2023.

by Sean O’Toole