The past few years have been a time of reform and reinvention in the art world. In South Africa, a multigenerational group of women photographers have been cap- tivating audiences and garnering plaudits. Enigmatic Zanele Muholi and Jo Ractliffe, two respected mid-career photographers, have both had their work surveyed by prominent museums in London and Chicago respectively.

Young photographers like Phumzile Khanyile and Lebohang Kganye have also been making headlines, this after clinching important early-career awards and showing up in all the right places. While their work ranges in style from gritty documentary to experimental studio-based pieces, the four photographers share a common connection to The Market Photo Workshop, a photography school, gallery and project space, founded in 1989 by David Goldblatt. ‘It never ceased to excite me,’ Goldblatt told me of the work he saw produced by the workshop’s graduates. Increasingly his excitement is being shared and experienced by a wider public.

JO RACTLIFFE

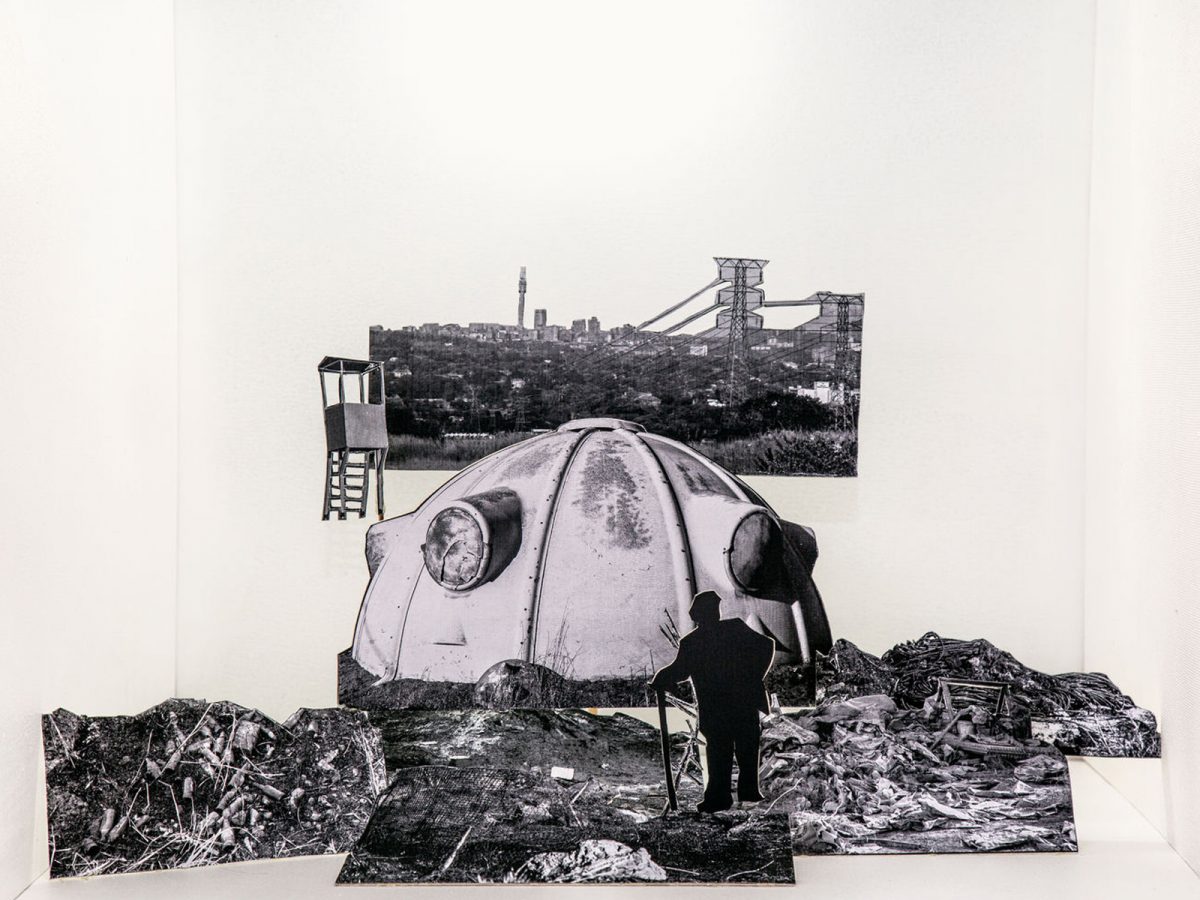

A pioneer of experimentation in photography, Jo Ractliffe (b. 1961) started out producing black-and-white photos. The landscapes of her native Cape Town featured prominently. In the late 1980s, she began experimenting with photo- montage, a shift that proved liberating. ‘I could reconfigure my photographs, as- sembling various elements from different pictures to create an image that retained something of photographic veracity but that could also speak metaphorically to what felt like an apocalyptic time in South Africa,’ she said.

Heralded by the influential Nigerian- American curator Okwui Enwezor as ‘one of the most accomplished and underrated photographers of her generation’, Ractliffe’s photos and lesser- known videos are currently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago in the US.

The exhibition, the first-ever international survey of her work, charts Ractliffe’s development from wandering modernist observer of Cape Town’s shabby urban periphery to innovative recorder of Johannesburg’s post-apartheid flux. After a period working in colour, Ractliffe returned to black and white in 2007 for a pro- ject documenting contemporary Angola. She has produced two further bodies of work exploring the aftermath of South Africa’s long and ruinous war with Angola.

‘My interest is not in the immediacy of the moment and the thing in front of me,’ Ractliffe once told me. ‘It is always the stuff that circulates around it, the felt experience.’

ZANELE MUHOLI

Unquestionably South Africa’s most renowned contemporary photographer, Durban-born Zanele Muholi (b. 1972) initially studied PR before enrolling at the Photo Workshop in 2001. A year later, Muholi, who uses the gender pronouns ‘they/their’, co-founded the Forum for the Empowerment of Women, the first black lesbian rights organisation in South Africa. These two events – the decision to study photography and mobilise against homophobic abuses – have deeply influenced Muholi’s subsequent career.

‘In the face of all the challenges our com- munity encounters daily, I embarked on a journey of visual activism to ensure that there is black queer visibility,’ Muholi has said, yielding the descriptor they are most known by: ‘visual activist’.

Muholi’s earliest work was largely docu- mentary in nature, addressing the reality of homophobic hate crimes, but included hints of the lyricism and autobiography of their later work. After graduating from the Photo Work- shop, Muholi drafted Goldblatt to be their mentor. He later paid for Muholi’s postgradu- ate studies at Ryerson University in Toronto. ‘Some of us grew up without fathers,’ Muholi once told me of Goldblatt. ‘He filled that role, in a way. I could be me, and I had no reserva- tions. Every criticism made me produce qual- ity work.’

Muholi first achieved international promi- nence with their project Faces and Phases (2006-ongoing), individual portraits of black lesbians exhibited in large groupings. Muholi’s current widespread acclaim is built on their self-portrait series Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail, the Dark Lion- ess). Started in 2012 in Cape Town, and made on the fly in cities globally, the self-portraits feature props (wooden pegs, pool pipes, bicycle tyres, straws) and employ heightened contrast. ‘By exaggerating the darkness of my skin tone, I’m reclaiming my blackness,’ Muholi said.

‘I think that the things Muholi deals with in relation to race and representation, queer histories and creating counter archives, is really important and speaks to a particular moment that has touched a lot of people,’ says curator Sarah Allen, who co-organised a recent survey of Muholi’s work at London’s Tate Modern. ‘The self-portrait series is just incredibly strong as well.’ Acclaimed Johannes- burg photographer Jodi Bieber, known equally for her gritty assignment work and ennobling portraits of women, is effusive: ‘I absolutely love and adore Zanele’s self-portraits. They are so visually striking and dynamic.’

LEBOHANG KGANYE

Ekurhuleni-born Lebohang Kganye (b. 1990) wanted to be a writer, not a photographer. When her application to study journalism at Wits University was rejected, she enrolled in a photojournalism course at the Photo Workshop in 2009, the idea being that she would later reapply for journalism.

One year turned into two, then three, and, well, journalism’s loss has been photography’s gain. A rising star in international photography, Kganye has bagged a slew of awards, including the Camera Austria Award for Contemporary Photography in 2019, and the 2020/21 Grand Prix Images Vevey, a prestigious European photography prize with a R650 000 purse.

‘Kganye has a practice deeply informed by the concerns and techniques of master artists from South Africa including William Kentridge, David Goldblatt, Sam Nhlengethwa, and Zanele Muholi,’ remarked the Images Vevey jury in reference to her imaginative practice, which draws photography into conversation with printmaking, sculpture, video and performance.

For all its cross-disciplinary wandering, Kganye’s practice remains rooted in photography, in particular archival photos from personal family albums. In 2012, two years after her mother’s death, Kganye was awarded a Tierney Fellowship, a mentorship award adminis- tered by the Photo Workshop.

It enabled her to travel and meet with scattered members of the Kganye family, as well as work with artist Mary Sibande and curator Nontobeko Ntombela as mentors. This intensive process culminated in her 2013 exhibition Ke Lefa Laka (It’s my inherit- ance), which featured two highly original photographic projects.

The series Ke Lefa Laka: Heir-story (2013) shows Kganye wearing her grand- father’s oversized suit, re-enacting family stories in an artificial cityscape. Ke Lefa Laka: Her-story (2013) presents Kganye superimposed into old family snapshots depicting her mother, mimicking poses while dressed in her mother’s clothes. Influential German photography collector Artur Walther acquired a full edition of the latter series.

Kganye’s method of inhabiting and animating family photos remains the basis of her much-admired practice. She also remains wed to literature. Her new work for Images Vevey, a large-scale theatri- cal installation using archival photos, will be launched in late 2022 and references Malawian writer Muthi Nhlema.

PHUMZILE KHANYILE

The youngest of the pick here, Soweto-born Phumzile Khanyile (b. 1991) has been winning awards and influential fans for a 2016 body of work made in her grandmother’s home. ‘Being raised by my grandmother, who had stereo- typical ideas of what it means to be a woman, often left me feeling suffocated,’ says Khanyile, adding that photography became a way to negotiate her ageing caretaker’s haranguing. ‘My grandmother never understood photogra- phy, so I would photograph in secret whenever she was at church or asleep.’

First exhibited at the Photo Workshop in 2017, Khanyile’s photos in her Plastic Crowns series mingle autobiography with a playfulness usually only seen in fashion photography. Presented again earlier this year at promi- nent French photo festival Rencontres d’Arles, Plastic Crowns includes two self-portraits of Khanyile with Nicki Minaj-like blonde hair.

The politics of black hair is a recurring interest. Plastic Crowns also includes a photograph of Khanyile wearing a red shoe belonging to her mother; only her left leg appears in the frame. New York curator Antwaun Sargent, author of The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion (2019), is a fan. He included Khanyile in a group show in Arles this year. Fashion offers just one lens for appreciating Khanyile’s work, which is resonant with generational and gender strife.

By Sean O’Toole