From talking animals in his stop-motion animations and his use of ‘not-quite-real’ periods in history to his ability to create places that feel familiar but don’t in fact exist, filmmaker Wes Anderson has a visual sensibility all of his own. Known for creating ornately detailed and sometimes strangely symmetrical sets that themselves feel like meticulously designed art installations, Anderson’s films possess an unsubtle quality that sets them apart from reality, a distinctive look that is entirely handmade and fastidiously controlled, almost hermetically sealed.

To his fans, Anderson’s idiosyncrasies are pure delight. Detractors, though, consider the Texan-born-and-raised director’s style laboured, nitpickingly fussy, perhaps too mannered and outlandishly oblique. They regard his characters as cartoonish. And the storylines? Absolutely bonkers.

On top of precision control and fastidious attention to detail, noticeable are the striking colour palettes, quirky framing, curious patterns and the requisite round-up of actors who do deadpan so successfully. Which also makes him meme-worthy and ripe for imitation.

And while many have tried and failed to replicate his cinematic style, he’s well represented in the real world.

Apart from myriad examples of the ‘Wes Anderson aesthetic’ in circulation via Instagram tribute accounts and books, there are also venues – hotels, restaurants, bars and boutiques – where Anderson’s striking colour palettes, rigorous symmetry and idiosyncratic visual kookiness are honoured, parodied or recreated. There’s Bar Luce, a Wes Anderson-designed café at Milan’s Fondazione Prada. Closer to home, a French bistro in central Cape Town, named The Wes, has a look inspired by The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), and then there’s Camp Canoe, a glamping resort situated at Boschendal near Franschhoek that’s styled as a homage to his 2012 film, Moonrise Kingdom.

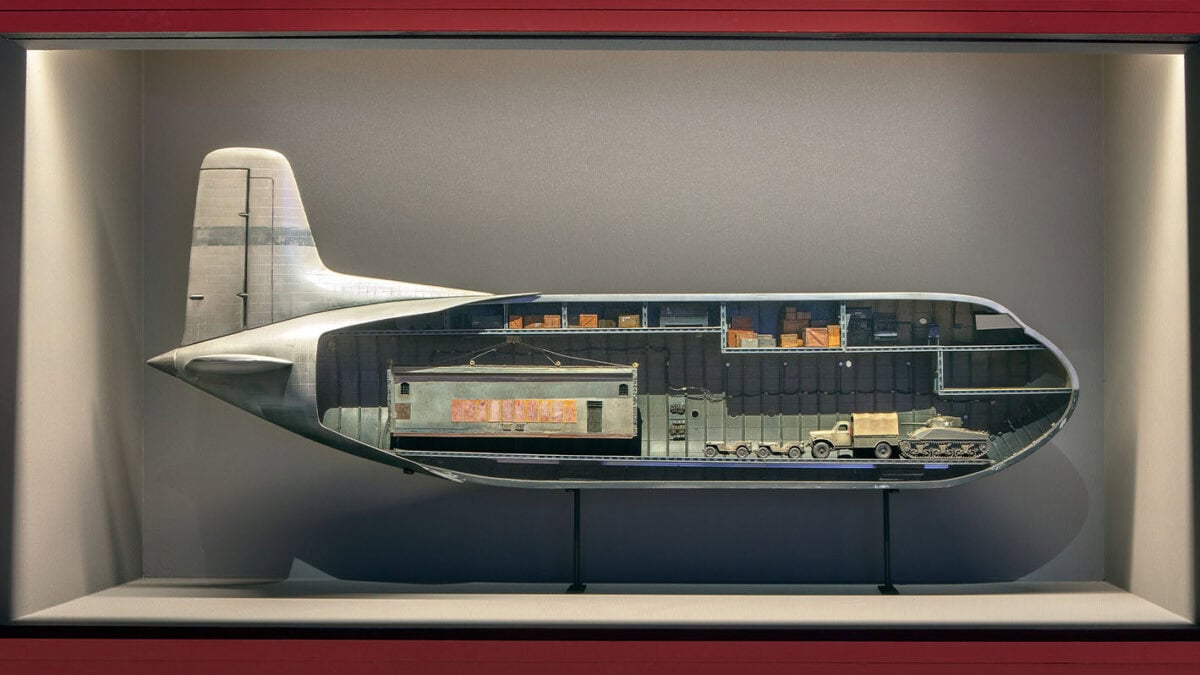

Anderson is known for having his collaborators meticulously handcraft objects from across just about every department of his productions, from zany submersibles and strange underwater creatures constructed for The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004), to the uniquely realistic puppets made with real animal fibres for Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) and Isle of Dogs (2018). For both canine-themed stop-motion animations, puppet-makers toiled over each and every whisker to achieve precisely the look and feel that Anderson’s perfectionist eye demanded.

Some of the objects constructed for his films are seen on screen for mere moments, but such is the obsessive nature of his crafted aesthetic: he gets involved in the tiniest details, such as tweaking the colours and fonts used to create magazine covers that appear on screen for a few seconds in The French Dispatch (2021). He’s had his art team create a fake Kandinsky and a Klimt. And in The Grand Budapest Hotel, considered by many to be his seminal (and most Oscar-worthy) feature film, there’s an entirely made-up faux-Renaissance-era painting, ‘Boy with Apple’ (purportedly by the non-existent artist Johannes Van Hoytl the Younger), that’s a key part of the film’s narrative.

‘Each of his films plunges the viewer into a world with its own codes, motifs, references, and with sumptuous and instantly recognisable sets and costumes,’ says Lucia Savi, co-curator of ‘Wes Anderson: The Archives’, an exhibition of some 600 objects that have been selected and exhibited to showcase the depth and breadth of the filmmaker’s contribution to cinema. ‘Every single object in a Wes Anderson film is very personal to him — they are not simply props, they are fully formed pieces of art and design that make his inventive worlds come to life.’

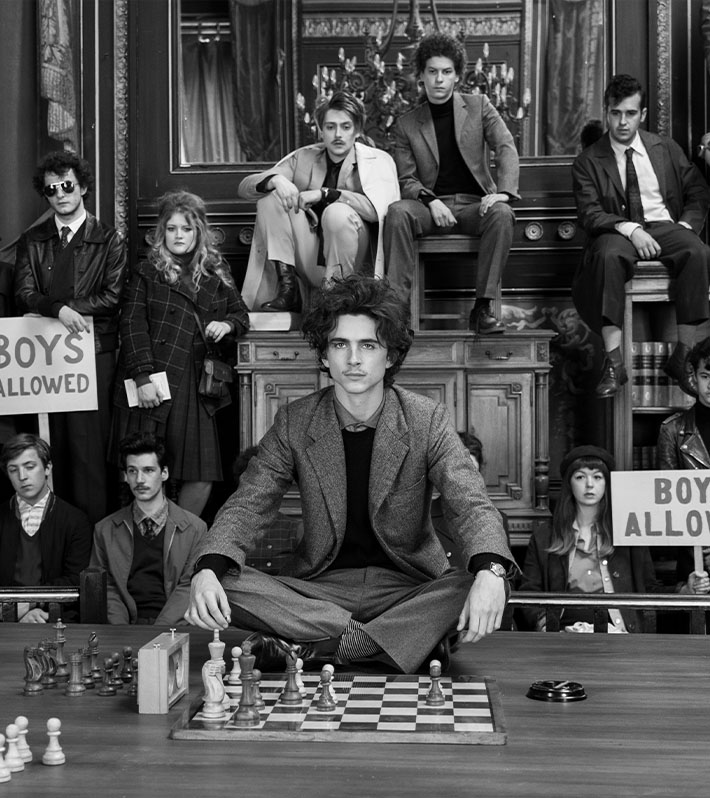

The exhibition debuted earlier this year at the Cinémathèque Française, a film museum and cinema in Paris. In November, it reopens at The Design Museum in London where it will show until mid-2026. The exhibition includes all manner of production artefacts – costumes, props, miniature models, artworks, décor elements, puppets – as well as storyboards, polaroids, sketches, paintings and a vitrine full of the director’s yellow spiral-bound notebooks filled with ideas jotted down in his distinctive capital letters and his hand-drawn miniature storyboards.

The collection exists thanks to Anderson’s fastidious archiving of objects used in his films after the props from his first film, Bottle Rocket (1996), were sold by the studio without his knowledge – and before he could shoot pick-up scenes. After Anderson made Rushmore (1998), he began hoarding all the props, costumes and set pieces from his films, and keeps them in a storage facility in Kent, England.

Exhibition highlights include the model of the pastel-pink Grand Budapest Hotel; a mix-and-dispense martini vending machine from Asteroid City (2023); painted Louis Vuitton luggage and model train cars created for The Darjeeling Limited (2007); the khaki suit, red tracksuit and mink Fendi coat worn by Gwyneth Paltrow in The Royal Tenenbaums (2001); the fantastical sea creature puppets and pale aquamarine uniforms from The Life Aquatic; and then there’s the fantastic Mr Fox himself, wearing his signature corduroy suit.

Among Milena Canonero’s Oscar-winning outfits from The Grand Budapest Hotel, there’s Ralph Fiennes’s Gustave H concierge costume, as well as the coat, dress and accessories worn by ancient heiress, Madame D, who was played by Tilda Swinton.

Also being exhibited is ‘Boy with Apple’, the ‘priceless Renaissance portrait’ that Gustave H inherits from Madame D, a regular hotel guest whom he’d been seasonally ravishing while still alive. The painting, though, doesn’t in fact refer to any historic work in the real world – it was commissioned specially for the film and created by British artist Michael Taylor.

What visitors won’t see, however, are several genuine artworks featured in Anderson’s most recent film, The Phoenician Scheme, which premiered at Cannes this year.

In contrast to Anderson’s usual insistence on creating from scratch every object in his films, The Phoenician Scheme includes brief cameos by pricey real-world masterpiece paintings. In the film, these actual artworks, captured on celluloid for mere moments in order to establish a mood and convey some unspoken meaning, belong to the wealthy-but-shady industrialist Zsa-zsa Korda (a deadpan-hilarious Benicio del Toro), who, in one scene, shares some sanguine advice. ‘Never buy good pictures,’ he tells one of his sons. ‘Buy masterpieces.’

Korda’s fake-real art collection includes Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Impressionist portrait of his young, long-haired nephew. Titled ‘Enfant assis en robe bleue (Portrait d’Edmond Renoir fils)’ and painted in 1889, it was once owned by Greta Garbo whose estate sold it at auction in 1990 for $7 million; today it belongs to a family of serious collectors. And there’s René Magritte’s ‘The Equator’, depicting a grey house plant that seems to have birds for leaves. Painted in 1942, it might have been contemporaneous with Korda’s own timeline, hinting at some inadvertent luck he has with collecting. Also featured are real paintings borrowed for the production from Germany’s Hamburger Kunsthalle, among them a 17th-century still life by Floris Gerritsz van Schooten, of a roast ox on a breakfast platter.

For a cinematic universe in which so much is invented and fabricated from scratch, it’s unusual for Anderson to have insisted on using real paintings, but he says the works were there ‘to be themselves’ in an environment where everything and everyone is pretending to be something else. The artworks were the only objects truly being themselves.

That Korda has quite haphazardly amassed such a valuable art collection but barely bothered to hang most of the pictures, hints at their utilitarian function – as commodities for investment – for someone who has spent his life accumulating material wealth. Perhaps, too, they’re a clue to a key distinction between Korda, the careless tycoon, and Anderson, the filmmaker who cares so much.

Cares enough, in fact, that each film frame might be considered its own momentary masterpiece.

Not that Wes Anderson’s world is limited by the borders of his films’ frames. Far from it. The aesthetic sensibility and visual humour embodied by his films in fact exist in the real world – often evident in plain sight.

While the actual Grand Budapest Hotel doesn’t really exist, just about anywhere you look it’s possible to run into accidental manifestations of Anderson’s universe.

This uncanny relationship between reality and fiction has of course spawned an Instagram account – AWA (Accidentally Wes Anderson) – which is populated by crowd-sourced photographs submitted by fans, photographers and just about anyone with an eye for detail and a knack for spotting examples of Anderson’s visual style in the wild. The account has shared more than 2 000 images of actual places that look like they might be stills from one of his movies.

Motivated by followers’ interest in ‘the unique, the symmetrical, the atypical, the distinctive design and amazing architecture’ that pervade Anderson’s films, AWA has produced two volumes of a coffee table book and ‘Accidentally Wes Anderson: The Exhibition’, which has shown in Los Angeles, Seoul, Tokyo, Shanghai, Melbourne and London.

AWA co-founder Wally Koval calls the travelling photographic exhibition ‘a journey through more than 200 of the most beautiful, idiosyncratic and interesting places on earth – all seemingly plucked from the whimsical world of Wes Anderson’.

Whimsy may define him, but Anderson is also an artist in the reverential sense of the word. Whatever apparent irreverence pervades his films, it would be ridiculous to call them frivolous. Even at their most gloriously pastel-pink, cartoonish and playful, Anderson’s movies grapple with deeper issues (and torments).

The Grand Budapest Hotel, for example, may look like a silly romp about a clever concierge with playboy tendencies, but it’s also about a fascist takeover – borders closing, random arrests and the erasure of civility. And Isle of Dogs concerns the consequences of a corrupt dictatorial mayor who has banned all the city’s dogs to an abandoned island. These films don’t, at first glance, look like political pictures but they are allegorical accounts of rising authoritarianism.

The Phoenician Scheme, meanwhile, walks a kind of kinky narrative tightrope pitting capitalism against spirituality. It’s not without that Anderson signature: a comedically convoluted plot with a lot of magnificent silliness and fun for fun’s sake. But it is also heavily laced with existential dread and a restless fascination with mortality. The film is marked by stark, surreal black-andwhite dream sequences – shades of hallucinatory Luis Buñuel, and hints of dreamy Michael Powell – in which Korda experiences visions of funerals and the afterlife. Even God is there – played by Bill Murray. (Who else?)

Pressed to try and explain the source of his seemingly obsessive meticulousness and control, Anderson says that he’s simply unable to work any differently, that over the years he has become, in a sense, ‘more Wes Anderson’. Even if he were to deliberately avoid making ‘a Wes Anderson film’, he says, he would sabotage himself in order to create a picture that looks like one of his.

In other words, whatever’s processed through him automatically gets the Wes Anderson treatment.